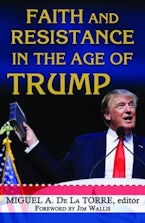

Faith and Resistance in the Age of Trump

Edited by: Miguel A. De La Torre

272 Pages

- Paperback

- ISBN: 9781626982475

- Published By: Orbis Books

- Published: September 2017

$22.00

Since the 2016 election, it is difficult to ignore the sense of fatigue washing over people in activist and academic circles nationwide. Developments in the Russia investigation reveal the fragility of our democratic processes, budget cuts and resignations strip executive departments of their effectiveness, and the bombastic ramblings of this new president threaten to unravel the safety and security of the entire nation, but especially of vulnerable populations. Many watching the events of the last year are understandably exhausted. But, as the contributors to Faith and Resistance in the Age of Trump remind us, this is not the time to shut down or turn away; this is not the time to become disillusioned or apathetic; and, this is especially not the time to allow our despondency to foster inaction. This volume, edited by theologian and ethicist Miguel A. De La Torre, is comprised of twenty-five short chapters, each by leading theologians, scholars, activists, and religious leaders who approach the topic of faith and resistance from their own disciplinary as well as personal perspectives. In the immediate post-election period in which much of the blame for Trump’s win was placed on the putative overzealousness of “identity politics,” these contributors wear their subjectivities on their sleeves. They challenge media pundits who attributed Trump’s victory to negligence of the “everyman” (a thinly-veiled euphemism for white, Christian, heterosexual, cisgender men). Contrary to such commentators, the contributors to this volume critique the “everyman” position as one of privilege: to inhabit an identity not inherently political or politicized is a luxury to which many in this country are simply not privy. It is to these non-privileged bodies—bodies now made even more vulnerable by a Trump presidency—that we should now attend. This volume is a guide, a “roadmap,” as Jacqui J. Lewis tells us in the preface, for how to do just that (xxv). Those looking for an in-depth analysis of the topics covered in this volume may hesitate at the brevity of each chapter. But what this volume perhaps lacks in exhaustiveness, it gains in accessibility and digestibility. This volume is not written for academic readers alone—though they will certainly find much useful discussion within its pages—but is primarily written for religious communities. The purpose of this volume is to address and to motivate religious communities in the US to act according to the principles of their faith and to resist the discriminatory and violent policies being instituted by this administration. At its core, this volume is a call to action. It is meant to reach people, to inspire anyone committed to social justice to act on that value by doing something, by saying something. Each author approaches this objective differently and chooses to address different areas of concern under this administration—for instance, racial justice, immigration status, LGBTQ rights, reproductive health, voter suppression, environmental degradation, unequal and unfair economic policies, and so on. But, despite this topical breadth, the urgency of resistance is a common thread uniting each chapter. For the contributors to this volume, resistance to systemic oppression is a religious act, an act of faith. This theme frames the book and is repeatedly revisited throughout. For example, in the preface, Lewis characterizes resistance to empire as a form of prayer, a form of prayer akin to Jesus’s spiritual revolution, which developed alongside—and informed—his resistance to Roman imperial rule (xxiv). Also speaking to this notion of resistance as a religious act, Marie Alfred-Harkey describes resistance as a moral imperative in her chapter on sexual justice. For Alford-Harkey, to resist injustice is to empathize, to use one’s religious values to defend those vulnerable to institutional prejudice and violence (68). Simone Campbell, in her chapter “Low-Wage Workers and the Struggle for Justice,” echoes this theme by equating political activism with “holy curiosity” (44). To take an interest in the stories and well-being of others, Campbell argues, is to partake in something holy. This theme concerning the faithfulness inherent to resistance is at its most poignant when it is applied to issues of institutional violence and (white) privilege. Many chapters in this volume address the ways that oppression creeps into the fabric of everyday life and numbs us to the dangers of its effects. This is especially egregious, this volume argues, when oppression is enabled by those claiming to be moral leaders of their communities. This volume aims to shine a light on the complicity of religious leaders who, with their silence, condone Trump’s prejudice and vulgarity. Such leaders, in the words of De La Torre, “prostitute” themselves to an immoral leader in exchange for political power and sway over the Supreme Court (xxx). David P. Gushee and Jim Wallis mirror this sentiment in their chapters, criticizing white evangelicals who traded in their faith and so-called moral values for legislative influence and cultural dominance. As Wallis argues, the fact that Trump was able to mobilize the white Christian vote, despite his obvious bigotry, xenophobia, and misogyny, demonstrates that racial solidarity proved more influential than the Christian maxim to love one’s neighbor (157). Another notable thread running throughout this volume is the palpable passion of its contributors. Each chapter, each example of resistance, is not just an examination or dissection of our current state of affairs but is also an attempt at catharsis. This volume is not just analytical; it is also indignant, mournful, and reconciliatory, sometimes all at the same time. Though it is, as De La Torre empathizes in the conclusion (230), sometimes hard to be hopeful, this volume reminds us that it is especially in such times that we are required to speak—to speak up and to speak often. But, even more than to speak, this volume calls us to act. This is a necessary read for anyone looking for a way to make hope a political reality once more. Kirsten Boles is a doctoral student in Women's Studies in Religion at Claremont Graduate University and Assistant Editor of Reading Religion. Kirsten BolesDate Of Review:February 27, 2018

Miguel A. De La Torre is professor of social ethics and Latino/a studies at Iliff School of Theology in Denver, CO. An ordained Southern Baptist minister, he is the author of 18 books, including Reading the Bible from the Margins, Trails of Hope and Terror, and Introducing Liberative Theologies.

Faith and Resistance in the Age of Trump was published by Orbis Books in 2017. I had a chance to speak with the editor of this collection, Miguel A. De La Torre, at the AAR annual meeting in Boston in November of that same year. —Troy Mikanovich, Assistant Editor

TM: What started this project? And what was the process like, reaching out to your contributors?

MT: Last year at the AAR everybody was depressed and distressed.

TM: That was right after the election, right?

MT: Yes, about two weeks after the election. People were walking around in a daze, stress eating, cursing…and as we were witnessing this among all our colleagues—well maybe not all, but most of our colleagues—I started thinking about how to redirect this energy. Do scholar-activists have something to say at a moment such as this? Is there a word we can proclaim in the midst of so much anger and despair and frustration with what’s happening in the nation? So, I quickly ran over to Orbis Books and asked, “How fast can I get a book out?” After they laughed, they said if they could get all the articles in by February, maybe they could get the book out by September. So I said, “OK.” Then I started contacting some colleagues I know, and some that I don’t know whose work I greatly respect, who I thought really have a good grasp of looking at the moment through theoretical lenses. Then I also sought individuals from diverse communities which this particular presidency was definitely going to impact. After the initial shock, most of the people that I invited said yes, and literally put their current work on hold to get an article for the volume to me by February 2017.

TM: Can you speak to the theme of “complicity” that seems to run through each of these pieces?

MT: “Complicity” is where this project began. We each began our chapters asking, “How were we complicit with what happened?” And then, from there we tried to end each article with specific things to do: In which praxis should should we engage? What is it that we need to be thinking about? How should we be responding? There was a very clear format for each chapter, and everyone pretty much kept to the structure. It makes the entire book feel more interconnected, rather than the sense of reading through a set of unrelated opinion pieces.

TM: I think that complicity point is an interesting way to frame this work, because while there’s been a lot of talk in the media about resistance to the current administration, I don’t know that much of it starts from such a reflective place.

MT: I wanted the reader of this book to find a voice with which they could resonate, among the variety of voices in the volume. And in that resonance, find a voice also saying, “Look, we as a group also screwed up here, this is our responsibility, and this is what we need to do.”

TM: And that story looks different for different groups, right? Because a trend throughout the election was the overwhelming support that Donald Trump received from conservative evangelicals. But you still have a diversity of authors—not all of them evangelical—who are claiming some complicity with Trump’s election.

MT: Absolutely. For example, you mention evangelicals, David Gushee wrote the section on evangelical Christians, and he begins with the 81% who voted for Trump. Susan Thistelthwaite is writing about white women, and she’s talking about how 53% of white women who voted for Trump. Miguel Diaz talks about the Catholic complicity with Trump. This really allowed us to not just write from the position of “What did you all do?” but rather “What did we all do?” I wanted to make sure we had a multitude of voices, a multitude of perspectives, faith traditions, ethnic groups, and racial groups in order to really enrich the conversation. One of the things we were hoping to accomplish is clarify that the same structures oppressing Latinx folk are the same exact structures oppressing black folks, or white women, or Muslims. That even though we’re dealing with these social structures that seem to isolate oppression, it’s all interconnected. The hope is that as someone reads, they can say, “Oh! I relate to that, even though it’s not my story.”

TM: That structural critique is something that I really appreciate about this book. A lot of people have focused on the fact that Trump is “outside the mainstream,” but it seems like this book goes behind that and argues that there’s something wrong with the mainstream.

MT: Absolutely. I mean, Trump takes it to a new level. I don’t want to minimize this. But at the same time, I don’t want to get to a point where we convince ourselves that other previous presidents were not also white supremacist. For example, one of the articles dealing with the Latinx experience reminds us that Obama was known as the “deporter-in-chief.” Obama deported more individuals than all the previous presidents, Republican included, together. It’s not like things were going great for us, and now all of a sudden we have Trump. Things were going badly, and now we have something even worse. We didn’t want to make Trump an exception to the rule: he’s an extreme example of what was already occurring.

TM: It seems like the conversations that the authors are having in this collection can be connected to your previous work. In Embracing Hopelessness, for example, you discuss the prospect of upsetting oppressive social structures in the face of a hopeless world. Do you see those same themes coming through here?

MT: I do. As a matter of fact, both books were being written at the same time. My whole theme of hopelessness and the embracing of hopelessness rests on the realization that neoliberalism has won. Racism has won. None of this is going to be fixed in my lifetime, or in my children’s lifetime. It really is a hopeless situation. Any hope that I may have that we’re somehow going to overcome this is just used to domesticate me, to ensure that my praxes are not radical.

I could hope that I could survive this, I could keep my eyes down, I don’t make noise, I obey the rules, but the end is still the same: death. The hope of being set free is used to make sure I don’t upset the apple cart too much; hope means that I might have something to lose. But when I have nothing to lose, that’s when I’m the most dangerous. If I’m going to die anyway, that’s when I’m willing to take those radical actions that need to occur for radical change to happen.

The last chapter of Embracing Hopelessness is a certain four-letter word which begins with the letter “F” and ends with “K.” In Spanish it’s joder: it’s to screw with systems. I’m talking about an ethics para joder. When the structures are rigged against you, when you’re going to lose anyway, the only thing you really can do is screw with the systems. It’s Jesus turning over the tables at the temple. The question, then, is how can we do this ethically?

Applying this survival ethics to the Trump book: What do we do now that we have a Trump presidency? How do we screw with the presidency? Screw with the presidency in order to create a new situation, where new opportunities may lead us a little closer to justice, even knowing we may never get there?

TM: I know that right after the election, there was an argument made, usually by moderates and moderate conservatives, saying, “Well now he’s our president, and we support him because we support the country.” But an ethics para joder goes against that, right?

MT: Absolutely. Supporting something that brings death to portions of our population is not being a good American, it’s not having any love for country. And this is one of the things I believe we try to wrestle with in the book. For a lot of my white colleagues and friends, the Trump presidency is bad; but it’s mainly an inconvenience. They may lose some money, they may pay higher taxes, they may be angry. For the Latinx community, it means more death on the borders. And I’m not speaking figuratively. Literally more brown bodies are going to die. Right now, every four days, five brown bodies die in the desert. That number is going to rise under a Trump administration. For my black brothers and sisters, it means a justice department which will not care about black lives mattering. And, therefore, you’re going to have more black people being killed by law enforcement. For LGBTQI communities you have a State Department, a Justice Department that is against them. So, for some of our communities, it’s not an issue of inconvenience. For some of our communities, it means death. To support the president is to support the killing of my people.

TM: A lot of these chapters were somewhat speculative when they were written, when Trump had barely taken office. How do these chapters read that we’ve had year of President Donald Trump?

MT: When we introduce the contributors early on in the book, there’s a little paragraph I wrote that explains the situation: that everyone finished their article a month after the inauguration. And it says, ultimately, the reader’s going to be the judge. Was all this just hysteria, did we blow it out of proportion? Or, when you finally get this book, will it seem like we were right on target? And I think some of the articles, in all fairness, might have missed a point here or there, but I would say that the vast majority of contributions were spot on. They really got to the heart of the matter. Maybe some of them didn’t go far enough, because we couldn’t even imagine how low this presidency would go.

TM: Who should be looking at this book?

MT: You know, maybe with a certain degree of hubris, I would say everybody. Because it impacts everybody. And even those who support Trump will be challenged, I think. Probably the only chapter that really lets loose on Trump is my own. Everyone else has been very respectful in dealing with this crisis. Because it is a crisis, you know, and rhetoric is not going to fix. It really is a question of how we ought to strategize in order to prevent some of these things from happening.

TM: How would you like people to use the book?

MT: I know some churches have been buying the book in bulk and using it in a Sunday School class. You can read the book in one hand and have the newspaper open in the other hand, and even though the book was written eight months ago, it’s still relevant to what’s happening in the newspaper today.

TM: Outside of church cultures, I wonder if there isn’t a different conversation happening. Within secular culture, the inauguration of Trump is often discussed as a religious problem, as a problem born from evangelical complicity in his election. So how would you frame this book for a secular reader?

MT: One of the things I think the Trump administration is doing is putting the last nails into the coffin of Christianity, especially evangelical Christianity. Because this next generation, the millennials and Generation Z are so turned off by Christianity as the hypocrisy of the family values they preached. You know, the idea that Christianity hates homosexuals, Christianity hates immigrants, many of the younger generation want nothing to do with it. Think of the consequences. How many seminaries are closing right now? How many churches are empty? And if you go to a church, what’s the median age of the person in the congregation? Obviously, this was going on way before Trump came along. But I would argue he has definitely sped up the process: he’s made it more extreme, more problematic.

TM: Do you see the domestic resistance to Trump, of which your book is a part, tying into a larger international network?

MT: Yes, and we tried to bring this out in the book. Kwok Pui-lan wrote a chapter about China and Taiwan and what’s going on with America’s pivot away from Asia. We have at least two individuals who wrote about the environment, which is obviously a global phenomenon, and how Trump’s views have endangered both the planet and international relationships. Certain chapters also discuss the Muslim travel ban which, at that time the book was finished, was really exploding. George Tinker writes about Standing Rock, a situation which is connecting Canada with the United States. Donald Trump’s presidency is not just a domestic issue. It touches all nations, all people, and we see this as he travels around the world and the reactions he’s receiving.

TM: What kind of response are you hoping for with this book?

MT: The purpose of the book—the real goal of the book—is to provide some intellectual foundations for community organizing. For literally resisting, out of one’s own faith tradition, or lack thereof, an administration that is causing death to certain groups of people and the destruction of our planet. This is a moment where all of us have to step up to the plate, we all have to do something. Like I said, in 2016, everybody at the AAR was complaining and crying and gnashing their teeth, and that was OK. But if we’re still doing this a year later, then we deserve Trump, we really do. If we’re not actively engaged in making sure this presidency does not have a second life and a second term, then we need to get active now. One of the last things the book says is everyone needs to run for office. You know, we need scientists in Congress, helping us with the climate issue. We need teachers, we need professors, we need people of good will. We need more women running for office, more trans folks running for office, more Latinxs running for office, more black people running for office. We need to replace career politicians with citizens who really care about these issues.

I think we have a false dichotomy: that either you just do scholarship and study religion, and this is what makes you a rigorous scholar, or you engage in activism and you’re then not really scholarly. I think these are extremes and really do not help the conversation. Some disciplines, I understand, do not lend themselves to active social participation. If you’re asking, “What does a particular Greek word mean in a particular text?” and you have to spend years trying to unpack the particular nuance of that word, it may not necessary lead to social activism. That’s important work. I do not want to minimize this. But I’m a social ethicist; that’s my field. And in my field, if one is not engaged in the real-life issues of individuals, then I’m not quite sure how their ethical theories can be formed—they will be disconnected from the reality where people are actually living. But even for those in other fields, in their private lives, scholars of religious studies should be engaged as citizens of this country; they should care about what’s going to happen to their students. If they don’t want to connect their discipline to activism, fine. But as individuals they have a vested interest to be engaged and to participate in their scholarship, it surely not and either/or.