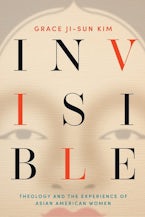

Invisible

Theology and the Experience of Asian American Women

By: Grace Ji-Sun Kim

177 Pages

- Paperback

- ISBN: 9781506470924

- Published By: Fortress Press

- Published: November 2021

$28.00

Asian American women in America have often found themselves with no voice and no choice in how they arrived there. Grace Ji-Sun Kim uses her own Asian American voice in Invisible: Theology and the Experience of Asian American Women to challenge this invisibility, and encourages other Asian American women to do the same. In this way, Asian American women can contribute to a growing understanding of “invisibility as a theological concept” (4). Kim accomplishes her goals of calling attention to the issue of invisibility through personal reflections, but her reflections are less helpful for Asian Americans who are not Korean American.

Chapter 1 sets up the rest of the book by laying out the issues that Asian American women confront alongside Kim’s own experiences. Kim details how Asian American women over many generations have not been able to speak out against injustices towards them. She declares that this silence must end and that Asian American women must speak up about the past. In acknowledging past experiences and oppressions, Asian American women also acknowledge continued injustices today. Kim attests to this reality by sharing her and her family’s experiences, a practice she continues throughout the book.

In chapter 2, Kim continues to detail the Asian American experience, focusing specifically on immigration to the US and Canada. This immigration experience shows how Asian American women have been forced into invisibility and liminal spaces, affecting their identity on various levels. Being forced into invisibility, as Kim highlights, creates “feelings of in-betweenness” among Asian American women (67). Operating from this space, Asian American women offer unique perspectives that have the potential to creatively change and challenge both society and the Church (68).

The next two chapters highlight specific aspects of racism and sexism, both familiar to Asian American women. Chapter 3 highlights Asian Americans’ experience of xenophobia and discrimination, which influence how they live their lives and navigate various aspects of society. Images such as the “model minority” and the “perpetual foreigner” have tended to sustain Asian American women’s experiences of invisibility (74). Along with these images, Asian American women have experienced hypersexualization, leading to certain sexual expectations of them from others, as well as influencing their own self-image. To counter this systemic racism, Kim argues that those on the margins need to move to the center, forcing society to confront marginalization (89–90).

In chapter 4, Kim addresses sexism primarily within Korean communities in America, as well as in her church experiences. She uses her experiences to describe how Asian American churches have perpetuated patriarchy and the subjugation of women, especially through the use of male-centered language and perspective to describe God’s character. After explaining the weight of sexism in these areas of Asian American life, Kim identifies the need for churches to acknowledge the sexism that has been and still is present in their own communities. In doing so, these churches can be “meaningful to women today” (122).

In the final chapter lies the core of Kim’s “theology of visibility,” which makes visible all those who have been made invisible (124). The method of doing this for Asian American women involves using Asian American terms in theology. Kim uses Korean American examples, describing the theological potential of the Korean concepts ou-ri (“our”), han (“unjust suffering”), jeong (“sticky love”), and Chi (“spirit” 139). This last chapter gets to the heart of Kim’s proposed theology, highlighting the need for intersectionality and inclusive language in the practice of theology.

Kim writes compellingly about the need to address the problem of invisibility among Asian American women. The strength of Kim’s overall work lies in her style of writing, revealing the reality of many Asian American women’s experiences through Kim’s own personal reflections. However, the inclusion of Kim’s personal experiences also gave the book a bias towards certain Asian American experiences, especially those of Korean American women. For example, South and Southeast Asian Americans tend not to experience hypersexualization in the ways Kim describes, an observation that goes unnoticed as she only features experiences from Japanese and Korean women (see 95-97). Further, the personal reflections throughout the book take away from the promised theological reflections, which were left primarily to the final chapter. Kim’s work would be better framed as a memoir, highlighting Korean American women’s experiences that contribute to a theology of visibility for Asian American women. In this way, Kim would have more closely aligned readers’ expectations with what she offers, and what Kim offers is substantial.

Re-orienting the practice of theology, as Kim urges, towards the margins is crucial for visibility, and Kim’s practical suggestions for incorporating Asian American terms encourage readers in their next steps. Invisible: Theology and the Experience of Asian American Women is valuable for those who want to begin understanding and responding to the experiences of Asian American people, especially Asian American women, in the practice of Christian theology. Kim draws necessary attention to the circumstances of many Asian American people, providing tangible examples and immediate solutions. This book leaves readers with a call to love continuously those forced into invisibility, just as God loves the invisible—as God’s own children, worthy of visibility.

Joy Clarisse Saavedra is a graduate student at Asbury Theological Seminary.

Joy Clarisse SaavedraDate Of Review:October 25, 2022

Grace Ji-Sun Kim was born in Korea, was educated in Canada, and now teaches in the United States. She is professor of theology at Earlham School of Religion in Richmond, Indiana. She is the author or editor of twenty books, including Hope in Disarray (2020), Intersectional Theology (2018), and Planetary Solidarity (2017). She is a coeditor for the series Asian Christianity in the Diaspora. Kim is an ordained Presbyterian Church (USA) minister and writes for Sojourners, Wabash Center, Baptist News Global, and Feminist Studies in Religion, and has published in TIME, Huffington Post, Christian Century, US Catholic Magazine, and The Nation.